The official U.S. Government view was expressed in an 1833 report by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to Congress: “The proneness of the Indian to the excessive use of ardent spirits with the too great facility of indulging that fatal propensity through the cupidity of our own citizens, not only impedes the progress of civilization, but tends inevitably to the degradation, misery, and extinction of the aboriginal race.” Despite that stern warning, brewers have used the names and images of Native Americans through the years to advertise and sell their alcoholic beer.

Displayed here are labels and ads all in that genre. The first is a trade card from the late 1880s and celebrates the Cherokee Brewery of St. Louis, boasted as gold medal winners and “Bottlers and Brewers of All Kinds of First Class Malt Liquors.” Now long gone but once located on the 2700 block of Cherokee Street, the brewery was accounted a massive complex built in the 1870s. Shut down by Prohibition, part of the facility later became a movie theater and later a parking lot.

Displayed here are labels and ads all in that genre. The first is a trade card from the late 1880s and celebrates the Cherokee Brewery of St. Louis, boasted as gold medal winners and “Bottlers and Brewers of All Kinds of First Class Malt Liquors.” Now long gone but once located on the 2700 block of Cherokee Street, the brewery was accounted a massive complex built in the 1870s. Shut down by Prohibition, part of the facility later became a movie theater and later a parking lot.

One of the more attractive images shows an Indian chief perched on a rock with a bow and arrow, gazing down at a lonely farm house. Yet nothing seems sinister, just romantic. It was the label of Reisch’s Sangamo Beer. But were the Sangamos a tribe in the vicinity of Springfield, Illinois? During the 1960s a site was identified nearby in official Illinois Archeological Survey files as “the extinct village of Sangamo Indians.” Later research has labeled that finding a mistake.

The Jacob Leinenkugel Brewing Company has made a great deal of a Native American heritage. It is made in Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin, the seventh oldest active brewery in America. The brewery is located adjacent the Chippewa River, located in Chippewa County, and according to the label the beer is made with Chippewa Water. For years their figurehead was — and still is —a Native American maid. The Chippewa, by the way, were a dominant tribe in the Upper Midwest.

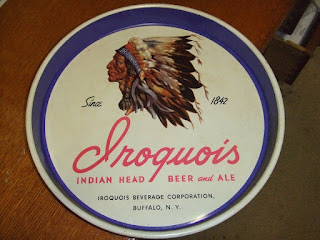

The Jacob Leinenkugel Brewing Company has made a great deal of a Native American heritage. It is made in Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin, the seventh oldest active brewery in America. The brewery is located adjacent the Chippewa River, located in Chippewa County, and according to the label the beer is made with Chippewa Water. For years their figurehead was — and still is —a Native American maid. The Chippewa, by the way, were a dominant tribe in the Upper Midwest. This advertising tray provides a vivid colorful side view of an Iroquois chief, appropriate branding for the Iroquois Beverage Company of Buffalo, New York. Its claim to be founded in 1842 is valid. It was the successor to the Jacob Roos Brewery, the name changed to Iroquois by a subsequent owner in 1892. It would become one of the oldest and longest-lasting breweries in Buffalo, surviving Prohibition by brewing soft drinks and near beer. With the reintroduction of real beer, Iroquois grew and prospered after Prohibition ended in April 1933. It became the largest brewer in Buffalo; eventually reaching a capacity of 600,000 barrels per year.

This advertising tray provides a vivid colorful side view of an Iroquois chief, appropriate branding for the Iroquois Beverage Company of Buffalo, New York. Its claim to be founded in 1842 is valid. It was the successor to the Jacob Roos Brewery, the name changed to Iroquois by a subsequent owner in 1892. It would become one of the oldest and longest-lasting breweries in Buffalo, surviving Prohibition by brewing soft drinks and near beer. With the reintroduction of real beer, Iroquois grew and prospered after Prohibition ended in April 1933. It became the largest brewer in Buffalo; eventually reaching a capacity of 600,000 barrels per year.

It is a wonder anyone would label a beer “Rosebud” and depict an Indian chief. The Battle of the Rosebud in 1876 was a long and bloody engagement in which the Lakota and Cheyenne fought with persistence and demonstrated a willingness to accept casualties rather than break off the encounter. The U.S. general barely escaped a devastating defeat. This beer was the product of the Harold C. Johnson Brewing Co. of Lomira, Wisconsin. Only briefly in operation, the company opened in 1945 and closed nine years later.

Another beer-maker that found it expedient to issue an advertising tray featuring a Native American, in this case a comely squaw, was the Wieland Brewery of San Francisco. A gold miner, baker and later “beer baron,” bought an existing facility, named it for himself, and built it into one of the largest and most successful breweries on the West Coast. Wieland himself died in a fire in 1885 and the brewery was sold to new owners who kept his name. Prohibition ended its operations.

Another beer-maker that found it expedient to issue an advertising tray featuring a Native American, in this case a comely squaw, was the Wieland Brewery of San Francisco. A gold miner, baker and later “beer baron,” bought an existing facility, named it for himself, and built it into one of the largest and most successful breweries on the West Coast. Wieland himself died in a fire in 1885 and the brewery was sold to new owners who kept his name. Prohibition ended its operations.

In a little known sideline, Dr. Seuss (Theodore Geisel) took a turn a putting a Native American into the beer trade. In 1919, on the very day his father became president of a Springfield, Massachusett brewery, National Prohibition was voted and eventually forced the brewery to close. Geisel never forgot the financial loss and trauma this event caused his family. Among his commercial drawings, Geisel did ads for beer and liquor companies.

in 1942 the Narragansett Brewing Company, located in Cranston, Rhode Island, asked Geisel to undertake an ad campaign for its beer. The president, Rudolph F. Haffenreffer, was an avid collector of Native American artifacts including cigar store Indians. Haffenreffer asked Geisel to weave an Indian theme into his advertising.

in 1942 the Narragansett Brewing Company, located in Cranston, Rhode Island, asked Geisel to undertake an ad campaign for its beer. The president, Rudolph F. Haffenreffer, was an avid collector of Native American artifacts including cigar store Indians. Haffenreffer asked Geisel to weave an Indian theme into his advertising. Thus was born “Chief Gansett,” a blocky figure wearing beads, carrying a hatchet and boasting a multicolored headdress. Most often this wooden Indian carried a large goblet of beer. The image proved very popular and the Chief appeared on a range of marketing items including trays, bar coasters, and posters as well as appearing in newspaper and magazine ads. In an ad for bock beer, Chief Gansett was depicted riding on an animal that bore a strong resemblance to a mountain goat.

Thus was born “Chief Gansett,” a blocky figure wearing beads, carrying a hatchet and boasting a multicolored headdress. Most often this wooden Indian carried a large goblet of beer. The image proved very popular and the Chief appeared on a range of marketing items including trays, bar coasters, and posters as well as appearing in newspaper and magazine ads. In an ad for bock beer, Chief Gansett was depicted riding on an animal that bore a strong resemblance to a mountain goat.

Stout Native Americans have also been summoned from time to time to help Anheuser-Busch sell Budweiser. As a colonist sits with his rifle, three Indians are vigorously poling a raft on which stand a chieftain with a barrel of beer at his feet.

Labeling the beer “The Chief of All,” the ad stretches to link the picture with selling the suds. Somehow because the chief represents “deeds of valor in war and wisdom in peace,” and Bud “quality and purity,” they both belong on the same page. The ad boys clearly had been imbibing when they thought up this pitch.

The same crew must have been at work on the next one. It has Pueblo Indians celebrating Thanksgiving. Once again Budweiser stretches for a Native American theme: “With joyous chants and throbbing tom-toms, the Indians celebrated each bountiful harvest of maize. How the red man would marvel to see the part his native grain plays in the nutrition and industrial prosperity of modern America!” How demeaning of Native Americans! It is as if there were no “red men” left in the U.S., all of them apparently eliminated (by alcohol?) in creating “modern America.”

The same crew must have been at work on the next one. It has Pueblo Indians celebrating Thanksgiving. Once again Budweiser stretches for a Native American theme: “With joyous chants and throbbing tom-toms, the Indians celebrated each bountiful harvest of maize. How the red man would marvel to see the part his native grain plays in the nutrition and industrial prosperity of modern America!” How demeaning of Native Americans! It is as if there were no “red men” left in the U.S., all of them apparently eliminated (by alcohol?) in creating “modern America.”

As has been seen here, the use of Native American images to sell beer could sometimes result in attractive images and artifacts, sometime in humorous, and sometimes in the ludicrous. But no such uses answer the concern raised at the beginning of this post about the effects of alcohol among indigenous Americans.