On June 15, 1882, the U.S. Patent Office received an application for a patent from William H. Maxwell of Rochester, Pennsylvania, a town not far from Pittsburgh. Maxwell, submitting the drawlng shown here, said he had invented “a new and useful improvement in the manufacure of Glass Paper-Weights and other Articles of Glass….” Granted a patent in September, Maxwell over the next six years produced myriad glass weights using his invention. As one writer has said: The Maxwell paperweight is a rare and treasured item for any collector to have in his possession.”

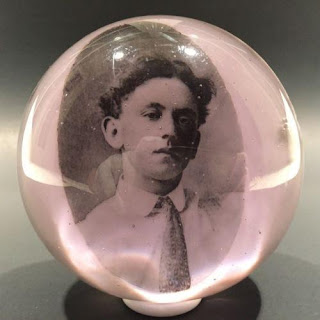

On June 15, 1882, the U.S. Patent Office received an application for a patent from William H. Maxwell of Rochester, Pennsylvania, a town not far from Pittsburgh. Maxwell, submitting the drawlng shown here, said he had invented “a new and useful improvement in the manufacure of Glass Paper-Weights and other Articles of Glass….” Granted a patent in September, Maxwell over the next six years produced myriad glass weights using his invention. As one writer has said: The Maxwell paperweight is a rare and treasured item for any collector to have in his possession.” Although I do not own a Maxwell weight, they have always fascinated me by their unique qualities of design and the fact that after Maxwell’s firm disappeared in the late 1880s, no other glassmakers subsequently have tried to replicate the effects he was able to achieve with his distinctive concave base and varying motifs captured in solid glass. Maxwell’s products may be divided into three categories. One were one-of-a-kind portrait weights with actual photographs of unidentified people encased in them, as the one shown here. Unfortunately, because they bear no identification of the subject, they are of limited interest.

Although I do not own a Maxwell weight, they have always fascinated me by their unique qualities of design and the fact that after Maxwell’s firm disappeared in the late 1880s, no other glassmakers subsequently have tried to replicate the effects he was able to achieve with his distinctive concave base and varying motifs captured in solid glass. Maxwell’s products may be divided into three categories. One were one-of-a-kind portrait weights with actual photographs of unidentified people encased in them, as the one shown here. Unfortunately, because they bear no identification of the subject, they are of limited interest.  The second category were weights that featured a business. These were mass produced — and probably the major profit center for Maxwell — for businesses who provided them to their customers for advertising purposes. Among the most interesting of those paperweights is one commissioned by the B. W. Wood & Bros. Coal Merchants of New Orleans. The main feature is a tug boat, apparently one of two owned by the company and named for members of the Wood family. A New Orleans Times-Democrat article of March 9, 1882, featured the owner describing him thus: “Wood is the prince of gentlemen and will pass anywhere as pure gold.”

The second category were weights that featured a business. These were mass produced — and probably the major profit center for Maxwell — for businesses who provided them to their customers for advertising purposes. Among the most interesting of those paperweights is one commissioned by the B. W. Wood & Bros. Coal Merchants of New Orleans. The main feature is a tug boat, apparently one of two owned by the company and named for members of the Wood family. A New Orleans Times-Democrat article of March 9, 1882, featured the owner describing him thus: “Wood is the prince of gentlemen and will pass anywhere as pure gold.” The next weight advertises the S. P. Shotter & Co, a businessman who began his company in Wilmington, North Carolina and later moved it to Savannah, Georgia. His company, among other things, made “brewer’s pitch” related to the yeast used in brewing. The major interest on the weight is the image of two small boys, possibly black, sitting on a barrel. Shotter probably would not pass as “pure gold” like B. W. Wood. According to news stories in May 1909, as chairman of the board of a company Shotter was sentenced to three months in jail and fined the equivalent today of $125,000 for violating the Sherman anti-trust law.

The next weight advertises the S. P. Shotter & Co, a businessman who began his company in Wilmington, North Carolina and later moved it to Savannah, Georgia. His company, among other things, made “brewer’s pitch” related to the yeast used in brewing. The major interest on the weight is the image of two small boys, possibly black, sitting on a barrel. Shotter probably would not pass as “pure gold” like B. W. Wood. According to news stories in May 1909, as chairman of the board of a company Shotter was sentenced to three months in jail and fined the equivalent today of $125,000 for violating the Sherman anti-trust law. Residing in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, the Metzger & Company roofers were neighbors to Maxwell’s glass blowing operation. One can imagine the owner visiting the factory to check out and approve the design, particularly the look of the roof feature. This weight, like others shown here was a large three inches in diameter and one and three quarters inches high. The pontil marks on these weights was smooth and fire polished, allowing some to bear Maxwell’s signature or a stamped maker’s mark.

Residing in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, the Metzger & Company roofers were neighbors to Maxwell’s glass blowing operation. One can imagine the owner visiting the factory to check out and approve the design, particularly the look of the roof feature. This weight, like others shown here was a large three inches in diameter and one and three quarters inches high. The pontil marks on these weights was smooth and fire polished, allowing some to bear Maxwell’s signature or a stamped maker’s mark. A final weight in the advertising category is from the Amazon Fire Insurance Company of Cincinnati. It shows a man on horseback with a spear lancing a fiercesome creature on the ground, ala depictions of St. George and the dragon. This horseman, however, seems to be naked from the waist up. This firm was headed by a president with the unusual name of Gazam Gano and reported $847,000 in assets for 1871.

A final weight in the advertising category is from the Amazon Fire Insurance Company of Cincinnati. It shows a man on horseback with a spear lancing a fiercesome creature on the ground, ala depictions of St. George and the dragon. This horseman, however, seems to be naked from the waist up. This firm was headed by a president with the unusual name of Gazam Gano and reported $847,000 in assets for 1871. The last and perhaps most interesting category of Maxwell weights were those one of a kind paperweights ordered by an individual or perhaps a group to be given to a specific person as a memento. Prominent among them is a item that depicts a railroad train in considerable detail, down to the number 544 on the coal car. It appears to have been given to John H. Doyle by a Miss Maggie Tattersall. Why? Were they sweethearts? Was this an engagement gift? The speculation can be endless.

The last and perhaps most interesting category of Maxwell weights were those one of a kind paperweights ordered by an individual or perhaps a group to be given to a specific person as a memento. Prominent among them is a item that depicts a railroad train in considerable detail, down to the number 544 on the coal car. It appears to have been given to John H. Doyle by a Miss Maggie Tattersall. Why? Were they sweethearts? Was this an engagement gift? The speculation can be endless. A second individualized Maxwell weight appears to have been made for a woman named Irene Zieg who apparently was competent enough in playing the coronet as to be allowed to play solos. The picture of the instrument seems well rendered and presented in two colors. It assuredly must have encouraged Irene on those dismal days when she brought her coronet to a party and no one asked her to play.

A second individualized Maxwell weight appears to have been made for a woman named Irene Zieg who apparently was competent enough in playing the coronet as to be allowed to play solos. The picture of the instrument seems well rendered and presented in two colors. It assuredly must have encouraged Irene on those dismal days when she brought her coronet to a party and no one asked her to play. Another professional based paperweight was provided to R. T. Betzold who presumably was a pharmacist in Baltimore. My initial efforts to find this Betzold through city directories of the time have been unsuccessful. The major element here is the mortar and pestle, often a symbol of the druggist trade. Again we have two colors, with green plants, perhaps themselves symbols of medicinal remedies, flanking the mortar.

Another professional based paperweight was provided to R. T. Betzold who presumably was a pharmacist in Baltimore. My initial efforts to find this Betzold through city directories of the time have been unsuccessful. The major element here is the mortar and pestle, often a symbol of the druggist trade. Again we have two colors, with green plants, perhaps themselves symbols of medicinal remedies, flanking the mortar. The final Maxwell paperweight was a gift to J. W. Hum, likely related to his activities as a Mason. I was able to trace him to a news item in which he is numbered among the men who founded a new Pittsburgh Masonic chapter, called the St. James Lodge. Hum subsequently was elected treasurer of the organization. This weight I consider the apex of Maxwell’s art. It is multi-colored, involving shades of yellow, brown and green, with a delicately crafted vegetative design. There are other weights with a similar motif, including one for “T.B. Wells, Chicago” and one with Maxwell’s own name on it and the date 1882 — marking when he first patented his invention.

The final Maxwell paperweight was a gift to J. W. Hum, likely related to his activities as a Mason. I was able to trace him to a news item in which he is numbered among the men who founded a new Pittsburgh Masonic chapter, called the St. James Lodge. Hum subsequently was elected treasurer of the organization. This weight I consider the apex of Maxwell’s art. It is multi-colored, involving shades of yellow, brown and green, with a delicately crafted vegetative design. There are other weights with a similar motif, including one for “T.B. Wells, Chicago” and one with Maxwell’s own name on it and the date 1882 — marking when he first patented his invention.

Maxwell’s professional career was filled with mishaps. In 1879 a fire at his glassworks destroyed the entire factory. His second effort was thwarted in 1883 when a problem with a furnace shut down the plant and caused him to put it up for sale. Even though he patented a second invention for improving printing on glass, mention of his firm ceases in the late 1800s. Maxwell's later years are unknown. For less than a decade, however, this inventive glassmaker provided hundreds of weights, now eagerly sought by collectors.