In 1956 the Lockeed Aircraft Corporation featured Thomas Hart Benton, whom they identified as “now one of our most celebrated painters,” in an ad for their Super Constellation airplane. Shown right, Benton at 67 was well into his career but, according to Lockeed, “still learning” and would fly their luxury liner to Rome the following year to study the European masters. Benton’s appearance in an ad is a reminder that he himself did advertising work — as did Norman Rockwell, Andy Warhol, and Dr. Suess — other artists featured on this blog.

In 1956 the Lockeed Aircraft Corporation featured Thomas Hart Benton, whom they identified as “now one of our most celebrated painters,” in an ad for their Super Constellation airplane. Shown right, Benton at 67 was well into his career but, according to Lockeed, “still learning” and would fly their luxury liner to Rome the following year to study the European masters. Benton’s appearance in an ad is a reminder that he himself did advertising work — as did Norman Rockwell, Andy Warhol, and Dr. Suess — other artists featured on this blog.

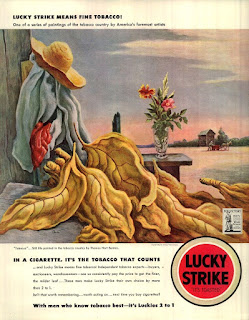

Benton has been hailed as America’s foremost regionalist artist whose figures of Americans at work, usually in mid-America, had an easily recognizable appearance, sinuous and sculpted. As a result of these qualities, the America Tobacco Company tapped him in the early 1940s to be part of its series for its Lucky Strike cigarettes that employed well-known artists to depict the country’s tobacco growing and processing. Benton obliged by painting at least four pictures in which tobacco was featured.

The first Benton artwork shown here is bereft of people, showing the discarded clothing and straw hat of a farmer who has harvested the giant tobacco leaves in the foreground. Appropriately, the artist called this painting “Tobacco.” Two elements are interesting. First, an incongruous vase of flowers dominates the center of the image. Benton painted this during the midst of World War II and the flowers may be a sign of hope. Less positive is the small figure of a farmer at the left, walking behind a mule-drawn cart, with a barn in the background — a reminder of the lack of mechanization in rural America.

The first Benton artwork shown here is bereft of people, showing the discarded clothing and straw hat of a farmer who has harvested the giant tobacco leaves in the foreground. Appropriately, the artist called this painting “Tobacco.” Two elements are interesting. First, an incongruous vase of flowers dominates the center of the image. Benton painted this during the midst of World War II and the flowers may be a sign of hope. Less positive is the small figure of a farmer at the left, walking behind a mule-drawn cart, with a barn in the background — a reminder of the lack of mechanization in rural America. Perhaps Benton was told by his corporate sponsors to make his next paintings more positive. Dating from 1942 the picture he called “Outside the Curing Barn” shows a hatted farmer affixing leaves of tobacco to wooden poles for hanging in the curing barn behind. The farmer’s dignified face and form were typical of Benton who romanticized American rural life while spending much of his time in Europe. In the background the farm hands are loading the mule cart — now two mules — with tobacco and the drying shed has a prominent place in the illustration.

Perhaps Benton was told by his corporate sponsors to make his next paintings more positive. Dating from 1942 the picture he called “Outside the Curing Barn” shows a hatted farmer affixing leaves of tobacco to wooden poles for hanging in the curing barn behind. The farmer’s dignified face and form were typical of Benton who romanticized American rural life while spending much of his time in Europe. In the background the farm hands are loading the mule cart — now two mules — with tobacco and the drying shed has a prominent place in the illustration. The next painting for Lucky Strike is quintessential Benton. The farmer is portrayed as an heroic figure with a strong body and a face winkled by toil, but yet gentle toward a little girl, presumably his daughter, a darling blonde child who appears to be asking him about tobacco. Note that the leaves are so thin that the girl’s hand can be seen through the surface. A mule and the drying sheds compete the scene.

The next painting for Lucky Strike is quintessential Benton. The farmer is portrayed as an heroic figure with a strong body and a face winkled by toil, but yet gentle toward a little girl, presumably his daughter, a darling blonde child who appears to be asking him about tobacco. Note that the leaves are so thin that the girl’s hand can be seen through the surface. A mule and the drying sheds compete the scene.  Benton’s art for the American Tobacco Company stretched over three or four years. Below may have been his last work in the series, published in 1944. Here the emphasis firmly on the farmer, in this case one who is sorting tobacco. From the slight smile he bears we can intuit that he enjoys and takes pride in this work.

Benton’s art for the American Tobacco Company stretched over three or four years. Below may have been his last work in the series, published in 1944. Here the emphasis firmly on the farmer, in this case one who is sorting tobacco. From the slight smile he bears we can intuit that he enjoys and takes pride in this work. World War II also saw American artists donating their talents to the war effort by painting images designed to sell war bonds, an important method of financing U.S. military forces while combating inflation at home. In 1943 Benton contributed this image of a young soldier about to embark on a transport ship that would be taking him into combat. With his blue bedroll slung over his shoulder he is looking directly at us — a typical American boy on his way to fight for his country. “He’s Going for You!” The least the viewers could do to help was to buy a bond.

World War II also saw American artists donating their talents to the war effort by painting images designed to sell war bonds, an important method of financing U.S. military forces while combating inflation at home. In 1943 Benton contributed this image of a young soldier about to embark on a transport ship that would be taking him into combat. With his blue bedroll slung over his shoulder he is looking directly at us — a typical American boy on his way to fight for his country. “He’s Going for You!” The least the viewers could do to help was to buy a bond. During the conflict, while cigarettes were strongly advertised, the liquor industry because of the need for alcohol in the war effort, kept a low profile. In the immediate postwar period, whiskey ads proliferated. The Hiram Walker distillery, that had originated in Canada but migrated to the States, sponsored a series of paintings by American artists and illustrators that ran in national magazines. The distiller apparently dictated that each picture feature barrels. Entitling his, “Whiskey Going in to Warehouse to Age,” Benton’s contribution is the most dynamic of the series, with one of his typical larger-than-life figures helping roll the barrels.

During the conflict, while cigarettes were strongly advertised, the liquor industry because of the need for alcohol in the war effort, kept a low profile. In the immediate postwar period, whiskey ads proliferated. The Hiram Walker distillery, that had originated in Canada but migrated to the States, sponsored a series of paintings by American artists and illustrators that ran in national magazines. The distiller apparently dictated that each picture feature barrels. Entitling his, “Whiskey Going in to Warehouse to Age,” Benton’s contribution is the most dynamic of the series, with one of his typical larger-than-life figures helping roll the barrels. “The Great golden wheat lands…rippling in the breeze…ripe for the harvest, Bountiful, beautiful — a vital part of the American Scene….Like these fertile, friendly fields, Maxwell House Coffee, too, is part of the American scene.” Yes, a stretch to equate a wheat field to the breakfast table, but that is what ad men are paid to do. In this case Benton did not paint the scene specifically for the coffee company so that he was not obliged to include elements dictated by the sponsor.

“The Great golden wheat lands…rippling in the breeze…ripe for the harvest, Bountiful, beautiful — a vital part of the American Scene….Like these fertile, friendly fields, Maxwell House Coffee, too, is part of the American scene.” Yes, a stretch to equate a wheat field to the breakfast table, but that is what ad men are paid to do. In this case Benton did not paint the scene specifically for the coffee company so that he was not obliged to include elements dictated by the sponsor.

As a result, it is the most successful of his advertising images.

Over the years Benton also did illustrations for the movie industry. The 1940 movie, the “Grape of Wrath,” is considered one of the great American cinematic masterpieces. Taken from the John Steinbeck novel, it is set in the Great Depression and is the story of the Joad family, forced to leave Oklahoma by drought and poverty to seek employment in California. For the movie poster, Benton captured the scene as the family loaded their ancient truck for the trip West. More poignantly than the book cover at left by a different artist, he captured the heartbreak in the departure.

Fifteen years later Benton would contribute a image to the poster of the movie, “The Kentuckian,” that both was directed by and featured Burt Lancaster. A story that was set in the 1820s, it concerned the travels from Kentucky of a man, his son and their dog, anxious to start a new life in Texas. Note that the gun and bedroll carried by the Kentuckian are reminiscent of those of the WW II soldier.

Fifteen years later Benton would contribute a image to the poster of the movie, “The Kentuckian,” that both was directed by and featured Burt Lancaster. A story that was set in the 1820s, it concerned the travels from Kentucky of a man, his son and their dog, anxious to start a new life in Texas. Note that the gun and bedroll carried by the Kentuckian are reminiscent of those of the WW II soldier.

The last Benton artwork shown here was done for a Coca Cola advertisement in 1964. This was the heyday of “The Twist,” a dance I never could get the hang of.

But the young people in the illustration clearly have all the moves, as they dance to the rhythms of a bongo drum. Although the table at the bottoms both cans and bottles on it, none of them look like Coke. In fact they look more like beer cans and wine bottles. By this time Benton was so well established as an iconic American painter, he could paint what he chose.

Known as well for the murals he painted, Benton continued to work well into his eighties. He died in 1975 while laboring in his studio as he completed his final mural, “The Sources of Country Music” for the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville, Tennessee. Today Thomas Hart Benton’s works can be found in museums all over the country — yet another noted American artist who found an outlet for his talent in the world of advertising.

No comments:

Post a Comment