The recent release of the motion picture “Ford vs. Ferrari,” based on the race car rivalry of the two automotive companies at Le Mans in 1966, has reminded me of the intense excitement races between two major competitors can engender with the public. The “Great Steamship Race” on Lake Erie in 1901 between the “City of Erie” and “Tashmoo” is a prime example.

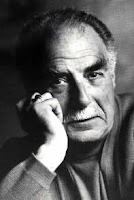

The initial irony of this race is that both contestants were the brainchild of a single marine engineer, architect and designer. Shown left, he was Frank E. Kirby, born in Cleveland, Ohio, who migrated to Detroit, Michigan, where he became a major figure in shipbuilding. Said an effusive contemporary biography: “Nearly one hundred of the largest craft upon our grand rivers and noble rivers are of his architecture and design, marvels of their kind and monuments to his ingenuity and skills.” They included the City of Erie shown below in a postcard view plying Lake Erie.

The initial irony of this race is that both contestants were the brainchild of a single marine engineer, architect and designer. Shown left, he was Frank E. Kirby, born in Cleveland, Ohio, who migrated to Detroit, Michigan, where he became a major figure in shipbuilding. Said an effusive contemporary biography: “Nearly one hundred of the largest craft upon our grand rivers and noble rivers are of his architecture and design, marvels of their kind and monuments to his ingenuity and skills.” They included the City of Erie shown below in a postcard view plying Lake Erie. Shown left under construction, The City of Erie, was launched in 1898 by the Detroit Dry Dock Company for the Cleveland Buffalo Transit Company. It is shown left under construction. The City of Erie's usual route was from Cleveland to Erie Pennsylvania, and on to Buffalo, New York. It was nicknamed the "Honeymoon Special" from the number of newlyweds who travelled to Buffalo, bound for Niagara Falls.

Shown left under construction, The City of Erie, was launched in 1898 by the Detroit Dry Dock Company for the Cleveland Buffalo Transit Company. It is shown left under construction. The City of Erie's usual route was from Cleveland to Erie Pennsylvania, and on to Buffalo, New York. It was nicknamed the "Honeymoon Special" from the number of newlyweds who travelled to Buffalo, bound for Niagara Falls. The Tashmoo was built two years later at a Michigan shipyard for Detroit’s White Star Line and launched on December 31, 1899. Tashmoo was nicknamed the "White Flyer" and, because of the number of windows on the ship, the "Glass Hack.” As shown here on a White Star Line flyer, the Tashmoo's regular route was the sixty miles from Detroit to Port Huron, Michigan, making several stops along the way. The photo below shows it leaving port with hundreds of passengers. Note that roundtrip tickets cost only 75 cents.

The Tashmoo was built two years later at a Michigan shipyard for Detroit’s White Star Line and launched on December 31, 1899. Tashmoo was nicknamed the "White Flyer" and, because of the number of windows on the ship, the "Glass Hack.” As shown here on a White Star Line flyer, the Tashmoo's regular route was the sixty miles from Detroit to Port Huron, Michigan, making several stops along the way. The photo below shows it leaving port with hundreds of passengers. Note that roundtrip tickets cost only 75 cents. The idea for a race arose in 1900 when two steamships on Lake Michigan engaged in a friendly duel and a Chicago newspaper branded both as “fastest on the Great Lakes.” That claim was disputed vigorously in other newspapers. The president of Detroit's White Star Line offered $1,000 to any ship that could beat the Tashmoo in a race. Shown here, J. W. Wescott, president of the C&B Transit Co. accepted the challenge. The course agreed on was 82 nautical miles (152 km; 94 mi) long, following the City of Erie's regular route from Cleveland to Erie.

The idea for a race arose in 1900 when two steamships on Lake Michigan engaged in a friendly duel and a Chicago newspaper branded both as “fastest on the Great Lakes.” That claim was disputed vigorously in other newspapers. The president of Detroit's White Star Line offered $1,000 to any ship that could beat the Tashmoo in a race. Shown here, J. W. Wescott, president of the C&B Transit Co. accepted the challenge. The course agreed on was 82 nautical miles (152 km; 94 mi) long, following the City of Erie's regular route from Cleveland to Erie.

News of the race engendered tremendous excitement, not only around the Great Lakes but nationwide. The Detroit Free Press branded it the “greatest steamboat contest in the history of American navigation.” The amount of money bet on the race was estimated to reach $100,000 — equivalent to at least $2.2 million today. Michigan bettors were known to have plunked down at least a quarter of that amount. Which ship Frank Kirby might have favored has gone unrecorded.

On the day of the race thousands of people lined the shores of Lake Erie from Cleveland to Erie. Thousands more crowded the railings of boats, large and small, anchored on the water along the race path. A photo shows the steamers facing off as the gunshot signaling the start was anticipated. The longer Tashmoo is far left, City of Erie next to it.

The race was timed with the City of Erie moving first. But the faster Tashmoo soon overtook its rival steamer and passed it. The Detroit Free Press described the scene below decks on both ships: “It was an awful strain on the crews of both boats, For five hours the engine room crews were shut in a hell hole….The heat was terrific….Strong men, subjected to the intense heat, became weak as babies, yet when told to surrender their shovels to others, refusing as they struggled gamely on.”

As the race progressed and the ships were out of sight of the shore, however, Tashmoo slowed, reputedly because the wheelman was not accustomed to steering only by compass. The City of Erie steamed past. With the shoreline visible again, the Tashmoo rapidly gained ground until an overheating condenser slowed it a second time. In the end, the City of Erie won the race by a mere 45 seconds. Tashmoo, however, was reckoned the faster steamer. Some blamed its loss as a jinks for being named for a doomed harpooner in Melville’s “Moby Dick.”

As the race progressed and the ships were out of sight of the shore, however, Tashmoo slowed, reputedly because the wheelman was not accustomed to steering only by compass. The City of Erie steamed past. With the shoreline visible again, the Tashmoo rapidly gained ground until an overheating condenser slowed it a second time. In the end, the City of Erie won the race by a mere 45 seconds. Tashmoo, however, was reckoned the faster steamer. Some blamed its loss as a jinks for being named for a doomed harpooner in Melville’s “Moby Dick.”

There was no return match although the Michigan owners asked for one. Cleveland’s Wescott refused, clearly understanding what the outcome might be. Both steamers went back to their usual routes, serving on the Great Lakes for decades. Their racing days over, each ship would have its travails.

In December 1927, Tashmoo snapped its moorings during a storm and headed up the Detroit River. Damaged and repaired, it later hit a submerged rock in the St. Marys River as it was leaving Sugar Island, Michigan. Able to evacuate passengers in Amherstberg, Ontario, it sank in eighteen feet of water and, as shown below, later towed to the scrapyard. In 1985 Tashmoo was named to the National Maritime Hall of Fame. A glass paperweight memorializes the vessel.

In December 1927, Tashmoo snapped its moorings during a storm and headed up the Detroit River. Damaged and repaired, it later hit a submerged rock in the St. Marys River as it was leaving Sugar Island, Michigan. Able to evacuate passengers in Amherstberg, Ontario, it sank in eighteen feet of water and, as shown below, later towed to the scrapyard. In 1985 Tashmoo was named to the National Maritime Hall of Fame. A glass paperweight memorializes the vessel.

City of Erie also met with ill fortune. In September 1909, it collided with and sunk a schooner, T. Vance Straubenstein. Three people on the smaller ship drowned. The steamer was retired from service in 1938 and scrapped in Cleveland in 1941.

Described in the press as “Two Freshwater Greyhounds,” City of Erie and Tashmoo represented the apex of steamship travel — and witnessed its decline. The coming of the automobile opened up new and more flexible travel options for millions of Americans. The steamers had taken almost five hours at top speed to go 94 miles. Soon motors cars could make it in two. Never again would a steamship race attract national attention. As “Ford vs. Ferrari” reminds us, gasoline-powered races soon would prevail.