The next two cards are, in effect, mirror images of each other. Two figures, identifiable as German youths are featured on each, although in different colored garb. Each is drinking from a large stein marked “Prosit,” German for “Cheers!” I am assuming that the button referred to in the text opens the spigot of a keg of beer. Otherwise the accompanying verse makes little sense: Dear Dutchy —

The next two cards are, in effect, mirror images of each other. Two figures, identifiable as German youths are featured on each, although in different colored garb. Each is drinking from a large stein marked “Prosit,” German for “Cheers!” I am assuming that the button referred to in the text opens the spigot of a keg of beer. Otherwise the accompanying verse makes little sense: Dear Dutchy —

Gersundheit and Prosit is all you can say

A button is all you can push

With your Rhine and your Nein

And your nose in a Stein

In the shade of the Anheuser Busch

Yet another reference to Adolphus’ company, is a postcard showing five gentlemen, all wearing porkpie hats, black coats, and a variety of checked pants energetically shoving forward a keg of beer with a spigot that it on wheeled wooden cart. It is captioned “The Anheuser Push.” While the title clearly is a play on words, the entire premise of what is intended here escapes me.

If Anheuser Busch was susceptible to puns so was the brewery’s principal brand, Budweiser. This card shows a scruffy black cat that clearly is experiencing a difficult situation or some dilemma. The caption here — “She was Pale ‘Bud-Weiser,’” — seems to be a variant on the theme “sadder but wiser” often used to refer to a young woman who ill-advisedly has engage in conduct with a young man that she now has reason to regret. Perhaps our cat has been caught by a prowling male.

If Anheuser Busch was susceptible to puns so was the brewery’s principal brand, Budweiser. This card shows a scruffy black cat that clearly is experiencing a difficult situation or some dilemma. The caption here — “She was Pale ‘Bud-Weiser,’” — seems to be a variant on the theme “sadder but wiser” often used to refer to a young woman who ill-advisedly has engage in conduct with a young man that she now has reason to regret. Perhaps our cat has been caught by a prowling male.

The names of other beers also could be used in pun fashion. Among them was Schlitz beer of Milwaukee — a rival of Adolphus Busch and his Budweiser. This card that combines the two. Here a newsboy is ogling a very pretty young woman sitting at an outdoor cafe drinking a glass of wine. She is wearing a dress that is slit on the side, showing ankle and calf. The boy is intoning: “Some like Budweiser but give me S’litz.”

A similar message is found on a another postcard. This time the lovely lass is standing and carrying a puppy. Nevertheless, the slit on her dress is revealing a stocking-covered ankle and leg. She is being followed by a vested young man with an eager look on his face, presumably taken by the sight of her shapely limbs. The female here seems pleased with the attention. Note that here “slits” is spelled correctly.

A similar message is found on a another postcard. This time the lovely lass is standing and carrying a puppy. Nevertheless, the slit on her dress is revealing a stocking-covered ankle and leg. She is being followed by a vested young man with an eager look on his face, presumably taken by the sight of her shapely limbs. The female here seems pleased with the attention. Note that here “slits” is spelled correctly.

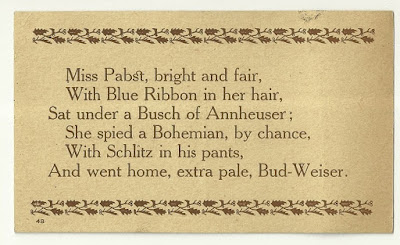

The notion of “Schlitz-Slits” could also offer more risqué interpretations, as demonstrated by the next two cards. Each is a poem, the first a true five-line limerick. In addition to ringing in Budweiser and Schlitz through their punning connotations, it brings in a third beer, Pabst, another Milwaukee product. Here the sexual innuendo is more blatant than with the cat scene.

This juxtaposition of St. Louis and the Milwaukee beers puts me in mind of the 1953 Milwaukee brewery strike that one Schlitz executive declared did “irreparable harm” to the city’s beer industry. During it, Anheuser Busch is said to have flooded Milwaukee with its Budweiser and gained many local patrons to the brand.

The next card presented a copy-cat verse, not a true limerick. It spelled “Busch” right and “Anheuser” wrong. The text referenced Pabst’s Blue Ribbon brand and brought in fourth beer, Bohemian, product of the National Bohemian Brewery of Baltimore, Maryland. In this doggerel, however, it is not so clear whether the implication is about a real encounter or just a glance by “Miss Pabst” that caused her to go home “extra pale, Bud-Weiser.”

The last card gives us a young woman who is very chastely dressed and carrying a bouquet of roses. This is a miss who would forego slits of any kind and never be “sadder but wiser.” The accompanying verse celebrates the home town of Anheuser Busch:

In old St. Louis on the banks of the Mississip’,

Where the Budweiser flows till goodness knows,

Its a wonder we dont all have the pip,

Where the pretty girls with their frills and curls,

Are on parade every day,

In the retail section on the eastern direction,

Bounded by old Broadway.

“We don't all have the pip.” Who wrote this stuff? The Simplicity Co. that published and copyrighted the postcard seem to have lacked editors. At least the art work was above average. I imagine if Adolphus had seen these items — most of them published in his day — he might have snorted rather than laughed. At the same time he might have been secretly pleased that Anheuser Busch and Budweiser were so prominently mentioned.