Recently the Washington Post ran a lengthy article on collectors of ephemera, that is, people who all kinds of items that are made of paper or other substances that were never meant to last over time. The word itself is from the Greek and means “for a day.” There is even an Ephemera Society of America with a sizable membership and a website.

These folks collect an amazing list of items. Among them are advertisements, billheads, stock certificates, trade cards, postcards, sheet music, photographs, bookplates, cigar box labels & bands, and greeting cards. The hobby is not a new one, having begun in England a century or more ago as the British developed colorful lithographic printing with elegant designs that were collected and often pressed into scrapbooks. Shown here is a particularly interesting early British trade card, currently valued at $800.

As American printers and design caught up to the Brits in the 1900s, American printers and lithographers began turning out attractive color images, such as the ad for the Colorado Rockies shown here. This card is in a university collection. Other U.S. trade cards, such as the Uncle Sam shown, here come up at auction frequently. Often they bring high prices.

Ephemera collectors sometimes can make innovative use of their hobby. One of them is Author Caroline Preston. Ms. Preston, shown here, is described as a “former archivist and keen collector of ephemera. She has employed her collection to give birth to a new literary form: a novel that revolves around ephemera. She calls it “The Scrapbook of Freddie Pratt.”

The story, laid during the “Roaring 1920s” in a type set narrative set among images of vintage paper items. Ms. Preston, a collector herself, uses illustrations from fashion drawings, valentines, cigarette ads, party game boards, prescriptions for medicine, and trade cards to tell her story. The novel has garnered a number of favorable reviews.

I suspect very few collectors could pull off what Ms. Preston has done. For most of us, ephemera ends up tucked away in scrapbooks or plastic paged albums or even file folders. When I first began writing articles for collector magazines in 1990, I mailed my manuscript to the publishers with numbered photos inside as the illustrations. Most of them were photographs that I had purchased or taken myself. Sometimes the photos were of ephemera I had been forced to purchase just to fill out a need for pictures. Many of those trade cards, ads, etc., are still tucked at various places around the house. A few were displayed in my July 2011 post on “Comin’ Thro’ the Rye.”

With the dawn of the Internet, however, a revolution has taken place. Author William Gibson, shown here, in an interview with the Washington Post on 2007 called it the “eBay era “ Gibson, who is credited with inventing the term, “cyberspace,” noted that “every class of human artifact is being sorted and rationalized by this economically driven machine that constantly turns it over and brings it to a higher level of searchability....It’s like some sort of vast curatorial movement.”

Gibson is dead right. Moreover, eBay, Google, and other sites are bringing to public view all manner of ephemera from bygone days and exposing them to public view. No longer are trade cards, labels, travel stickers, and old photos stuck away to be looked at by an individual collector when the mood hits. Now they are on public view 24-7 and often for sale.

For several years now, I have not mailed any photos. The illustrations for my pieces, like the text itself, fly over the Internet to my editors. In one instance, the final format of the piece is itself an Internet newsletter, sent to members of a collecting club. It never sees a “hard” copy. As a result of the changes the electronic age has brought, I have accumulated on my Mac several thousand images, most of them of ephemera. They grace my articles and fuel this blog and its companion blog: “Those Pre-Pro Whiskey Men.” I collect several images virtually every day, file them on the computer, and call them up when needed.

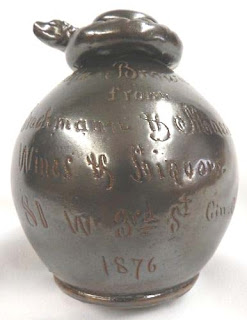

Recently for the whiskey man blog, I did a post on a man named Domenico Canale who created a liquor and food dynasty in Memphis, Tennessee. Much earlier I had come across a marvelous circa 1910 photo of a fruit vendor, which Domenico had once been, pushing a cart that advertised Canale’s flagship whiskey, “Old Dominick.” It was a highly useful image to put across visually the rapid rise of an Italian immigrant boy to financial success. I have filed the photo away on my computer to use in such other contexts as may arise in the future.

What is the bottom line for ephemera in an electronic age? Go digital, you collectors, go digital!